Dear Friend,

I hope you’ve had a good week. Spring is still playing with us here in Paris. On Friday, the sun was out and about, and all the Parisians had followed it onto the café-terraces: it felt like we could finally declare spring sprung. I saw one Parisian woman stopped at a traffic light in the upscale 8th arrondissement on her bicycle. Her hair was perfectly coiffed, and while she waited for the light to go green, she was turning her face up to the sun so luxuriously that it looked like she was in a play. But then yesterday was all rainy and grey and the Parisians scurried back into their homes.

Still, it’s been a good, quiet week. Today I went for lunch with my dear pal Anna at Chiche, an Israeli restaurant in Paris’s busy 10th arrondissement. And now I’m writing from one of my happy places, a huge library complex called Mediateque Françoise Sagan (named after the prodigious French author who wrote Bonjour Tristesse). Earlier this week I had dinner with my French friend Diane, whom I met during the lockdown in 2020. She lived in the building opposite me and we started chatting at the 8pm round of applause for frontline workers.

Three years on, we’re still firm friends. My conversations with Diane are never dull. She’s a tiny woman (just under five foot, I would guess) with an abundance of intelligence and dry wit. I always learn something when I see her. This week, we were talking about how swear words are less strong/shocking in French. For example ‘con’, the equivalent of the ‘c word’ (the strongest swear word there is) in English is completely commonplace in French. It can be used as an adjective or a noun and means something like: ‘stupid’, ‘silly’, ‘daft’. You hear this word on the radio in the daytime, you could hear it in a work meeting, and even in film titles, like the light-hearted 1998 comedy ‘Le Diner de cons’. That movie is a farcical caper about a snobby Parisian editor who hosts a ‘fools dinner’. The word simply doesn’t have the same weight. One shudders to think that the film ‘C***s Dinner’ might involve.

There are other vulgarisms that make it into everyday conversation, too. The verb ‘foutre’, which translates as the ‘f word’ in English, but can also be used as a coloquial replacement for the verbs ‘to do’ or ‘to be (somewhere)’ e.g. ‘qu’est-ce que tu fous là?’ (what are you doing here?). And then there’s all the times that we’re unknowingly making scatological references when we speak French, like:

Comment ça va ? (How goes it?) — Originally came about in the Middle Ages when it was quite common to ask about the state of someone’s digestion;

Bon appétit — Same connotations;

Even more obscure, is the term for laughing ‘rigoler’ (‘je rigole’, ‘c’est rigolo’), which apparently comes from the word ‘rigole’ describing a small irrigation funnel/stream, evoking someone peeing themselves laughing.

This conversation with Diane helped me understand why French people swear so liberally when they speak English, in particular the ‘f word’, not realising how jarring it sounds to a native speaker. Of course, it depends on your sensibility. I come from a very un-sweary family and am particularly puritanical about these things.

On the dole

This week I have been listening to my dear friend Hattie’s podcast, ‘In Writing with Hattie Crisell’. If you are interested in writing, writers or the creative process, you will most likely like this podcast very much. Each episode Hattie interviews a famous author, from poets to novelists to scriptwriters to, recently, an obituary writer. It’s fascinating and she’s so good at extracting great stories and insights. (There is also a great newsletter to accompany:

).To be clear, Hattie is a busy freelance writer and is not on the dole, but I listened to the episode where she interviews the writer with novelist and non-fiction writer Geoff Dyer. I don’t know his work but I found his stories about how he started out in writing so interesting. He was born in the late Fifties, a classic ‘boomer’. He came from a working-class background and went to Oxford University. After he graduated, he spent a lot of his 20s living on “the dole” or unemployment benefits, which at the time were enough to live on. In his interview with Hattie, he talked about how that social security money helped him and other peers make a start in the creative industries. Today in the UK, Jobseeker’s Allowance is 60-80 pounds a week, certainly not enough to scrape buy on anywhere in the country, let alone London, which has become more expensive than anyone could have imagined in the Eighties.

In France, ‘the dole’ or as it’s called here ‘chômage’ is still something closer to what it used to be in the UK. That is to say, it’s a just-about liveable amount of money. Whether employed or running their own business, French people pay hefty social security payments from their pay; in return, they expect the state to provide a safety net for them.

Earlier this week, a man named Thibaut Guilluy, High Commissioner of Jobs/Employment, announced that Pôle Emploi, the administrative body that manages chômage will soon be rebranded as the more sexy ‘France Travail’. It’s part of a raft of razzle-dazzle measures being rolled out by Macron’s Government in the wake of the retirement legislation he has just pushed through — and the huge public backlash against it. Ostensibly, the change is meant to make it easier for unemployed people to get back into work, but it will also bring with it new obligations for job-seekers, including up to 20 hours of free labour per week in order to receive benefit. From a British perspective, it’s starting to sound familiar.

I know a lot of people outside of France are baffled by why workers and unions are kicking up such a fuss about the retirement reforms — a legal retirement age of 64 doesn’t seem all that dramatic. But, from what I can tell, it’s about more than just these retirement measures. Many French people think/feel that this is the tip of the iceberg. If they allow the existing social pact, based on a solid social security safety net, to be chipped away at, it’s only a matter of time until it will be dismantled completely. I read an interesting article that suggested that many French people see Macron as a kind of French Thatcher, determined to push through his agenda, whatever effect it has on hearts, minds and society.

It’s true that the unemployment payments here do seem very ‘generous’ compared to the more punitive UK system, and there are some elements of it I don’t totally understand at a technical level. For example, workers on very high salaries can continue receiving several thousand euros every month for a long time after their jobs end, if the termination is not considered to be their fault. I still have some research to do on the finer points of how this works. However, if a slightly flabby system is the price to pay for preserving breathing room for everyone (as Geoff Dyer describes) then I tend to think it’s well worth it.

Thirty-second book club

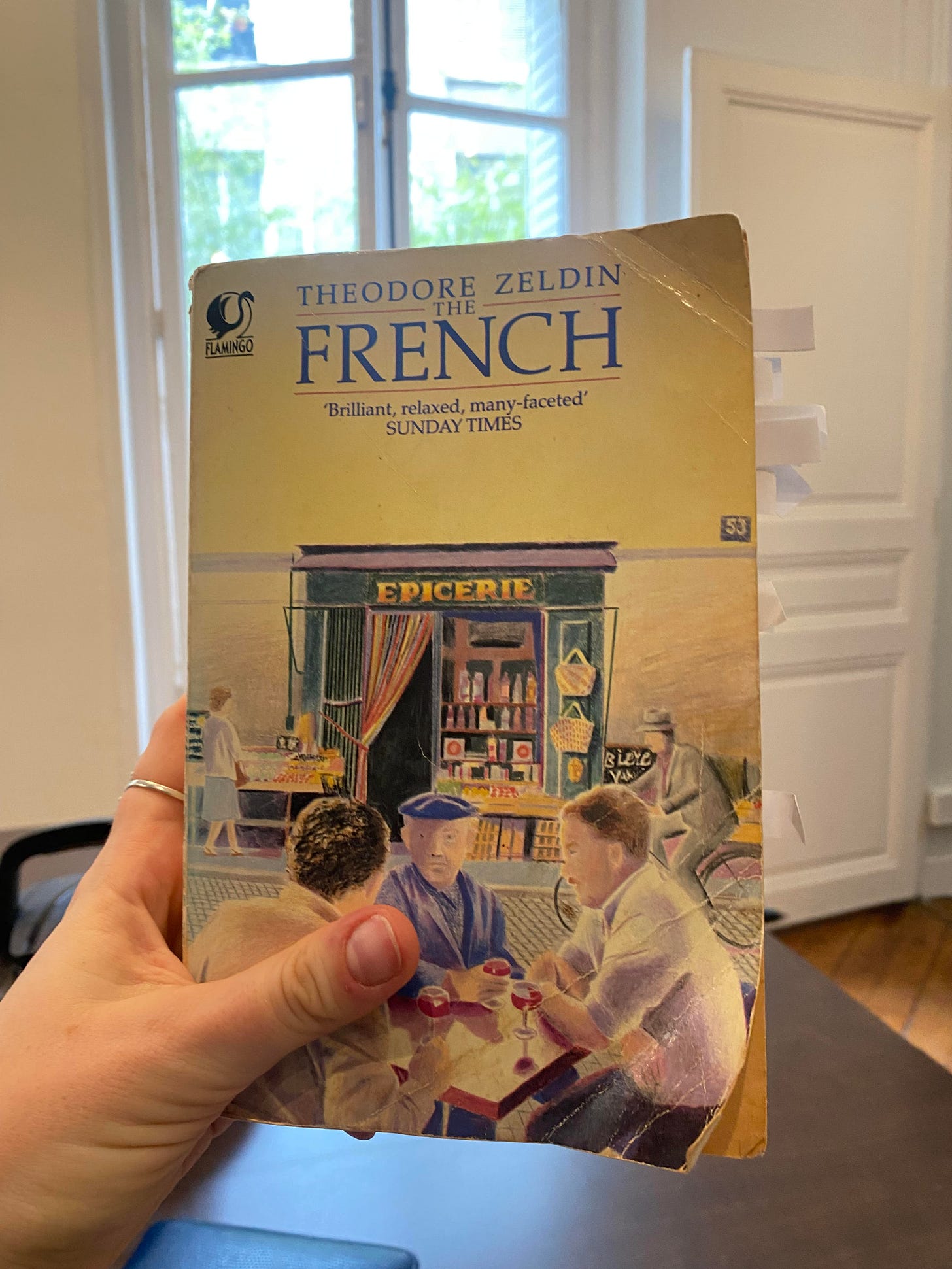

Spring in Paris is ‘brocante’ (antique sale/ jumble sale) season. As a lover of second-hand tat, I’m a big fan of these markets. At one such event last weekend, I came across a book simply called ‘The French’, written in 1983 by an academic and writer named Theodore Zeldin. Apparently he was quite well known in France in the Eighties and Nineties. I hadn’t heard of him before, but I have devoured his book and am now a committed mega-fan of the 89-year-old academic. It’s split up in to serval sections that explore different facets of (what was then) modern French life: Love and marriage/ Business and employment/ Arts and culture etc. It’s very interesting both for what is still so relevant and as a snapshot of a different time, right at the start of the fork in the road when Britain went Thatcher and France went Mitterrand.

Last week I wrote about the trials of French administration and bureaucracy (thank you to those who pledged solidarity with my post-office trials!). I like the way Zeldin summarises criticisms of French bureaucracy in the book:

“…Ministries and departments become rigid and isolated from each other,…the right hand does not know what the left hand is doing; that leads to periodic crises, and the whole system seizes up. Everybody then repeats that France is a ‘stalemate society’ and that deep down Frenchmen hate reforms but love revolutions; crises are the only way to get change.”

I found so much of this book interesting that I covered its pages with sticky notes. I haven’t finished yet, and may write more about it next week, only 40 years after its publication! Let it never be said that I don’t move with the zeitgeist.

Thank you for reading this letter about French swearing, the dole and The French (then and now). I hope you enjoyed it.

Please feel free to subscribe, sponsor, share, like, comment. Your interaction is much appreciated!

I will write next week. Have a good few days until then!

Yours,

Hannah

Loving your paintings this week Darling Hannah! Particularly the seductive green eyes of " younf French man". Having also been born. Intheblate 1950's( I know... fucking ancient, to bandy around with insouisance a swear word in English😂) yes, the " dole" was a fortune compared to the measly shambles which our society's underpriveledged are expected to survive on . I admire the French for not taking things lying down and always willing to make it known when they dissaprove of decisions

made by their leaders. I like the solidarity and bold fearlessness.

Its so interesting too to think why certain words cause such offence. I rather like the subversive naughtiness of the C word, I like the shock on peoples faces when they see an old woman being so disgraceful! Its also a great way to describe a person for which any other word simply wouldnt do!

Splendid read as always Hannah thank you so much . Love from Scotland and its deeply noisy wildlife ( STILL mating like crazy) x

Hi Hannah, a great Monday morning read for me as always, so thank you :)

Fascinating re: swearing. I also grew up in a very non-sweary family in the UK. I don't think I ever even dared utter the word "crap" around my parents and would probably still feel uncomfortable doing so. Such was their way and influence.

When I moved out of home and went to university, there was a lot more swearing for sure, but it wasn't until I moved to Australia that swearing was just everywhere. I don't think it's quite the same as in France, but there are certainly demographics here where c*** is an everyday word that can have all manner of meanings in expression (it's absolutely not one I'd ever use though. Most would still refer to it as "dropping the c bomb"). It certainly wouldn't ever dropped casually on radio during the day, but we just went to a show at the Melbourne International Comedy Festival and Ivan Aristeguieta did a whole bit about this and how it's part of Australian culture.

My question: are there *any* French swear words that are considered truly offensive/taboo?