Dear Friend,

I hope you’ve had a good week and that January is treating you kindly so far. If this is your first letter, welcome! I’m Hannah Meltzer, a British journalist living in Paris. I write and send these every Sunday and they also feature my drawings and paintings.

I am continuing to warm my winter evenings by watching Eastenders on BBC iPlayer, which as I said last week, I find distinctly cosy and nostalgic. Lovely Karen, who lives by Loch Fyne in rural Scotland wrote back to me last week after I spoke about the show in my letter. She said:

“Cosy old Phil Mitchell. My two [children] when they were young would go into the lounge with a plate of "mum chips" as a snack and shout out " Eastens," to the family so we would gather up together and see the shouting and general carrying on.

We loved it so much that [my daughter] called one of her rabbits " Janine" after The evil Janine Butcher.”

Thank you for writing, Karen, and I hope very much to hear a lot more about “Mum chips” and what they entail. Having recently started watching again, I can confirm that the evil Janine Butcher is still going, evil as ever, after all these years.

Pain points

In my last letter, I wrote mostly about how:

the energy crisis is particularly tough for France’s boulangers (bakers);

bread has a huge cultural and even political significance in France.

This week, two French friends, Diane and Adélie, wrote to me to share some extra morsels of information and cultural context about bread in France. Here are a few more things I learned:

A man named Steven Laurence Kaplan, an American historian who fell in love with Paris when he studied here in the Sixties, is France’s preeminent expert on bread. He has made the city his home and has written several books on the history of bread in French and English. He has even been an official judge for Paris’s best baguette contest, which I mentioned in last week’s letter. Here is how Kaplan’s first encounter with French bread is described in an article on the Princeton Alumni Weekly:

“Seeking lunch, Kaplan walked into Lionel Poilâne’s boulangerie near the Church of Saint-Sulpice and was overwhelmed. More than half a century later, he recalls that he ordered a bâtard, a torpedo-shaped loaf. “I can still feel it and taste it,” he says — still hear it, too, recalling its “melodic, crusty sound.” He carried the bâtard, a chunk of goat cheese, and a small bottle of wine to enjoy in the Luxembourg Gardens, but never got to the cheese. The bread was “so formidably defamiliarizing that I said to myself, ‘What is this?’”

My friend and neighbour Diane also told me about a very famous classic French film called La femme du boulanger, or The Baker’s Wife (1938). I haven’t had a chance to watch it yet, but have read a summary of the plot, which is wonderful. Aurélie, the attractive young wife of the local baker, who is named Aimable, i.e. ‘nice’, runs off with a dashing young shepherd. Immediately the peaceful Provence village falls into panic because Aimable is now too sad to make their bread. While the baker drowns his sorrows in pastis, the village organise to get Aurélie back to her husband as a matter of great urgency.

Another French phrase involving bread : “Bon comme du bon pain” or ‘good like good bread’, which means something like ‘good as gold’ or ‘a heart of gold’ or ‘thoroughly decent’. The highest praise possible, basically.

My friend Adélie told me about a famous French poem called Le Pain by a writer called Francis Ponge, who was known for his series of poems that minutely describe everyday objects. Here’s a taste:

FR: La surface du pain est merveilleuse

d'abord à cause de cette impression quasi panoramique

qu'elle donne : comme si l'on avait à sa disposition

sous la main les Alpes, le Taurus ou la Cordillère

des Andes. — Francis Ponge

EN: The crust on a loaf of French bread is a marvel, first off, because of the almost panoramic impression it gives, as although one had the Alps, the Taurus range, or even the Andean Cordillera right in the palm of the hand. — Translated by Lee Fahnestock,

Thirty-second book club

I’ve been reading a lot this week, but in a rather flitty, non-committal way, dipping in and out of several different tomes at the same time — this is not because each one is not gripping, but rather because each one is so interesting I keep getting distracted! One of them is a book that came out last year and that I’ve been excited about for a while; I asked for it from my mum for Christmas. It’s called The Story of Art Without Men and it’s by a young and brilliant art historian named Katy Hessel. I first discovered Hessel’s work through her excellent podcast, The Great Women Artists, and as I write this I have just learned that there is an accompanying Substack newsletter:

. Woohoo! Hessel's book revisits E. H. Gombrich's bible of art history, The Story of Art, but this time focusing on (often overlooked) women artists. It's a beautiful book filled with glossy reproductions of artworks from the Renaissance to the present day. The author writes wonderfully and so I'll pinch some of her words from the book's introduction to describe what it's all about:“The book takes its title from the so-called introductory ‘bible’ to art history, E, H. Gombrich’s The Story of Art. It’s a wonderful book but for one flaw: his first edition (1950) included zero women artists and even the sixteenth edition includes only one. I hope this book will create a new guide, to supplement what we already know.

Artists pinpoint moments of history through a uniquely expressive medium and allow us to make sense of a time. If we aren’t seeing art by a wide range of people, we aren’t really seeing society, history or culture as a whole”.

Previously in these letters I talked about Pablo Picasso and the juxtaposition between his often exquisite artistic output and his often seemingly dreadful treatment of the women in his life. In this context — especially thinking about how Picasso destroyed the artistic careers of some of some of his partners — I find Hessel’s book heartening and restorative. In the domaine of art, women have so long and so often been the object and this book gives these wonderful artists back their ‘I’, their subjectivity, their first-person perspective. And sadly, I still think this is needed and important and a big deal.

In the section of the book that covers Paris’s Belle Epoque, at the turn of the 20th century, Hessel describes the limitations faced by women in the Impressionist movement, like Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt; she explains that men could roam free around the cafés of Montmartre and paint whatever took their fancy, whereas women were expected to stay in the home more, and not go out and about unaccompanied.

It struck me that although things have changed for women, a century later in present-day Montmartre, we still can’t quite move about with the same heedless freedom that many men can. A woman still might have to contend with some/all of: being looked at in a way that’s uncomfortable, being talked at, being commented upon, being bothered or patronised or underesimated.

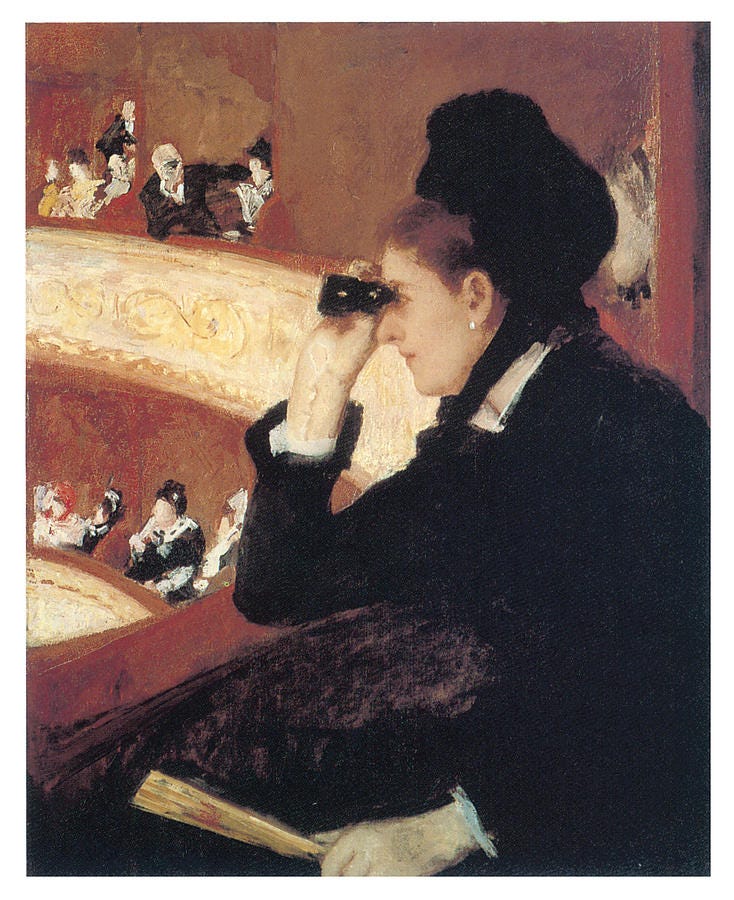

In her book, Hessel analyses a painting by Mary Cassatt called In the Loge, which depicts an upper-class woman watching the opera. I really like her analysis:

“A Parisian woman dressed in smart black ruffles peers through a pair of binoculars. Although it may appear that she is in charge of the gaze, as she is facing away from us … look again and the top left-hand corner reveals another onlooker also with binoculars …Ultimately, the message seems to be, woman is the spectacle: whichever way she looks, she is always controlled by a gaze.”

In the here and now, women’s art and. cultural contribution is definitely becoming more visible. Here are some interesting exhibitions currently on/ coming up this year in Paris:

Alice Neel at the Centre Pompidou (The last day is tomorrow! But it comes to the Barbican in London on February 16 until May 21)

Parisiennes Citoyennes! at the Musée Carnavalet (until 29 January)

Sarah Bernhardt retrospective at Le Petit Palais (April 14-August 27)

Surréalisme au féminin at the Musée de Montmartre (March 31-September 10)

*********

I have previously written about the idea of taking a sabbath day, free from outside intrusions, especially those brought by a mobile phone. I said that doing this may be the biggest luxury we can offer ourselves. Last week, I happened to come across an episode of the popular New York Times podcast, The Ezra Klein Show (Jan 3 2023) in which he interviews author Judith Shulevitz about her book The Sabbath World: Glimpses of a Different Order of Time. They also speak a lot about an older book, The Sabbath by Abraham Joshua Heschel, a Polish-born American rabbi, Jewish theologian and civil rights activist. I ordered both books; Shulevitz’s is still to arrive but Heschel came this week and I have begun it.

The Sabbath is an exploration of the Jewish practice of Shabbat, the day of rest observed from Friday sundown to Saturday after sundown. I have mixed ancestry with Jewish grandparents on both sides, so exploring that heritage is of particular interest to me — but actually what Heschel describes in the book is also relevant to the Christian day of rest (also part of my heritage on the English/Irish sides). In fact, it seems like it would be relevant to anyone interested in intentionally taking time out of their usual routine in order to reflect/gather with loved ones/remember who we are without noise and demands.

In the book, the author makes the distinction between the value we place on space (world-conquering, acquisition of goods etc.) and that which we place on time, arguing that to observe a rest day is to engage with an ‘architecture of time’. It’s a fascinating read and I will write a bit more about it after I’ve finished it, hopefully next week!

But at my back I always hear Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near; And yonder all before us lie Deserts of vast eternity. — From To His Coy Mistress, by Andrew Marvell (1621-1678)

That’s all for now! Thank you for reading this letter about bread, subjectivity, time and rest days. I hope you’ve enjoyed it.

If this is our first letter, please click below to make this correspondence a weekly thing.

Please share this letter if you like it, too. Thank you very much to Friend Peter N who was kind enough to share Pen Friend on his Instagram account. I was delighted! Do not be shy to do the same. I will lavish you with joyful emojis.

I’ll write again next week. I hope you have a good few days!

Yours,

Hannah

Great thiught provoking article as always dear Hannah,

I studied History of Art amongst my boffin years and it really made me think, I only had one large tome about an Italian rennaisance woman painter. Much saught after and with such a shocking and sad story to tell. She was brutally raped and of course had to carry that vile event with her .

Which also brought me to the awful fact that still, today so many of us are not as free as men to roam without vigilance. Its sad because there are really so many wonderful guys out there, its just as women we dont know which ones are safe.

I am 64 and still have to deal with leering unwelcome attention in taxis, at a cafe or even just popping in to see a matineee on my own.

Not always of course but it rather sours my private revelry where I do not wish to engage with unknown old blokes!

From a life time of daft cat calls and all the rest, I have learned how to live alongside this blasted nuisance at best, blasted real danger at worse.

When I was 15 I won a local poetry contest back in 1973 , the local rag interviewed me and I was all puffed up and ready to prate on about poetry etc etc,

The first question the ( male ) interviwer asked was " how does it feel to be a female writer?"

And life has pretty much been defined by that type of question in most aspects of my career

Sad to see its still very much a work in progress for us gals!

Thought provoking as always... also your water colours are lovely Hannah... more of Babs please ( mind the police dont arrrest her for being naked up there in Montmartre!)

Hi Hannah - happy new year. Really enjoyed the 'pain' theme. Still an issue of great sorrow for me, that a country that is about 15 miles away, at its nearest point, from La Belle France can't even begin to make an authentic French baguette ! Or at least I have never found anywhere, here, that can. Food and the streets of Paris, that you write so eloquently about, have reminded me of my student days sleeping rough under the bridge by Notre Dame, on the left bank, with friends, hanging out at Shakespeare and Co. and living off 'flan', baguettes and some sort of liquid cheese spread and, occasionally Tunisian sandwiches from the street vendors [no-one had any money in those days c.1971]. Happy days! Keep well.