Getting pistonned

The secret to success

Dear Friend,

I hope you have had a good week. If this is your first Pen Friend letter, welcome! I’m happy you’re here.

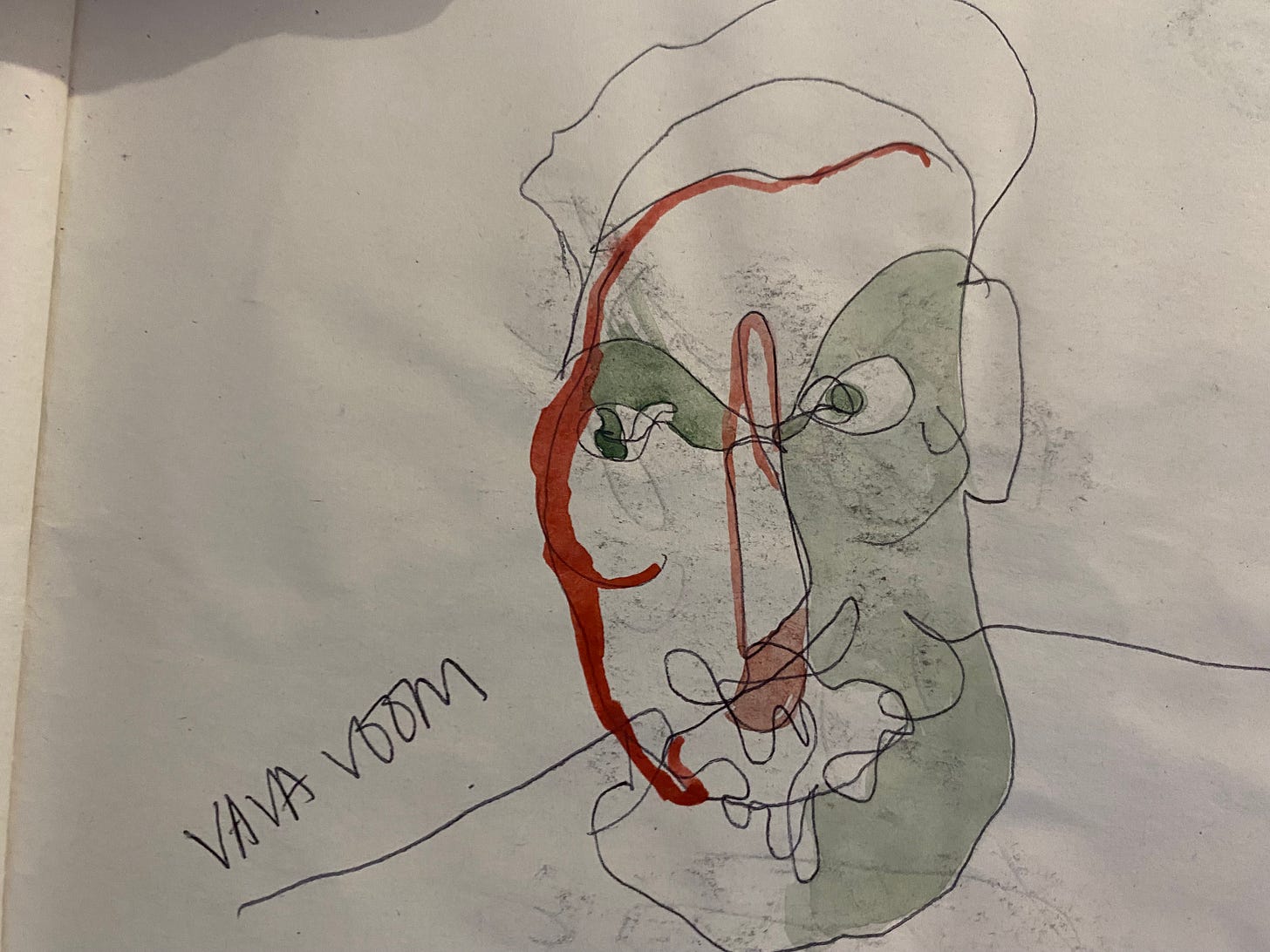

My idea with these letters is to talk about life in Paris as it really is today and to explore and unpack the clichés about it. Each letter also features my own original drawings. Voilà, now you know everything.

If we have been corresponding for a while now, then you will know I have been in the long and testing process of finding a new flat in Paris. Today, the dramatic action reaches a climax as this weekend is…moving weekend! (cue majestic music).

I wrote to you explaining about the importance in French life in general, and in the hunt for an apartment specifically, of the ‘dossier’—the file of paperwork that aims to prove that you are more financially solvent and trustworthy than your peers.

Now, it’s a paradoxical beast, because while French administration is paperwork-heavy, it also at the same time not really about what is on paper at all. That is to say, though assembling huge piles of documents is usually essential for getting anything done, the outcome can be, and often is, influenced entirely by the luck of an interaction between you and a person who has power to influence the decision.

In British culture we value, above all else maybe (?), a sense of ‘fair play’— the idea that there are certain rules and everyone agrees to stick to them. The Queue at the time of The Queen’s death really exemplified this. As I wrote then:

“It seems so fitting and unsurprising that the Brits would show mass grief in an extraordinary act of ordinariness. It is our way: be as weird as you like, but do it sensibly.”

I always think of my former commute, in particular the bus stops by Waterloo Station, where at least twenty different buses stop. Every morning during rush hour you’ll find multiple orderly queues of commuters forming. Each person autonomously orders themselves into neat lines in different directions, depending which buses they’re getting. I used to think this was just normal human behaviour—hat we all come out the womb with an innate knowledge of the silent rules of the queue. But…it’s not! When I first tried to queue for a bus in Paris, I learned this.

Here in France, the system is more relational than transactional or rules-based. You need your paperwork ready, but no matter how extensive it is, if the person in front of you doesn’t like the cut of your jib, then you’re not going to get anywhere. Now of course this allows for all kinds of discrimination and unfairness. What if the person in front of you only likes the cut of jibs of say, white people? Or men? Or people with nice teeth? Bah…dommage pour vous ! Too bad.

Here are some real-life examples of this relational, rather than formalised/transactional way of being:

Nationality application: A friend applied for French nationality. This is a lengthly process involving various stages of paperwork, language exams and so on. The final stage is an interview. I have heard wildly varying stories of what is asked at the interview and how strict the officials are. One friend told me that her interviewer just kept simply asking her the same question (“Do you have a lot of French friends?”) until she said the right answer (“Yes, I only have French friends”).

Doctors: Once I had to see an out-of-hours doctor. He seemed hurried and stressed until he saw that my name was Hannah. “Ah HAnnah!”, he exclaimed, emphasising the first syllable. “Hannah with an ‘H’, like HAnnah Arendt!!!”. For the rest of our appointment slot and ten minutes beyond, he spoke at length about his love of the German political philosopher Hannah Arendt.

Housing: And finally, to this latest example of the relational being most important. My new apartment! After spending hours making and worrying about our 30-page dossier, I got an unexpected call from a friend who lives nearby. There was a free apartment in her building and she had recommended us, meaning if we wanted the apartment, we could have it, because the landlady knew and trusted her. This is a perfect example of what the French informally call to“pistonner quelqu’un” or ‘to piston someone’ (pull strings for, make something happen for them). A person can also “être pistonné.e.s”, or “be pistoned”, as I was.

++All this is not to say that the British rules of fair-play and politeness lead to some kind of utopian meritocratic society. In fact, sometimes I think the coded-ness of how English people talk and behave leads to a particular type of passive aggression and even cruelty, but that’s a subject for another day!

Thirty-second book club

This week I read the The Silver Chain by Jion Sheibani, who was once my boss when I worked in her English school, and is now a pal. Using a mixture of verse and her own lyrical illustrations, Jion tells the story of Azadeh, a teenage girl of mixed Iranian and English heritage. The protagonist is grappling with her mother’s struggle with mental illness and finding refuge in classical music and her own violin playing. The Silver Chain reinvents the Young Adult genre in a book that is as a tender and complex as teenage girls themselves. It also made me wish I had not given up the violin aged 10 because I was too lazy/proud to practice!

Thank you for reading! I will write at more length next week when I am more settled into my new apartment.

Until then, I leave you with this meme I came across. It speaks about the process of finding a nice flat to live in in Paris. The caption reads: ‘Parisians in their studio flats looking out at their view over the bins for 1200 euros a month’.

Have a lovely week!

Yours,

Hannah

C’est Bon! Je parle Franglais ... 🤷♀️

To be fair re the violin practice – you were super busy with cross country.