Dear Friend,

Happy Easter! Sameach Pesach! Ramadan Kareem!

I hope you’ve had a good couple of weeks. As I mentioned at the end of my last letter, I’ve been away in Kenya and this is why I haven’t been writing weekly as I usually do. Thank you for your patience!

On the subject of my last letter, thanks to those who read my dedication to my mum’s career on her retirement and sent lovely replies. She spent the first couple of weeks of her freedom looking after my dog, Babbet while I was away, which I hope wasn’t too much of a burden.

I am back in London this weekend picking up the dog before heading back to Paris tomorrow. It is lovely and spring-like here, and apparently the same in Paris too. I seemed to have pulled off a smart trick of avoiding rain and bin strikes in Paris, as well as what the international media is describing as ‘riots’ (though my friends in Paris say their lives are largely unaffected by the largely peaceful and quite jolly protests about the pension reform).

Anyway, after a trip full of new people, impressions and landscapes, I am very glad to be going back to Paris in Spring, which I must admit is significantly superior to Paris in Winter. In fact, it’s my favourite season.

Eating life with a big spoon

My partner is from Nairobi, the capital of Kenya, and though we’ve been together for three years, the trip we just took was the first to Kenya in that time. It was marvellous. Kenya spreads out from a strip of the East African coast of the Indian Ocean. It is bordered by Ethiopia and South Sudan to the north, Somalia to the east, Tanzania to the south and Uganda to the west. It is roughly the same size as France, and like France, it is also home to a diverse range of geographies and peoples. There are 42 tribes, including the Kikuyu, Luhya, Luo, Kamba, Kalenjin, and Maasai.

Each official tribe speaks one or more local languages. The common languages are English and Swahili. The latter originally comes from the East African coast (spanning Kenya and Tanzania) and is a Bantu language (an African language family also including South African Zulu and Xosa), with a significant Arabic influence, some German, some Portuguese and quite a bit of English. Internationally, the most common words known in Swahili are hakuna matata, which, as children of the Nineties will know all too well, “means no worries” (for the rest of your days). From the same lofty source, Disney’s The Lion King, you may also know the word “simba” meaning ‘lion’ and “rafiki”, meaning ‘friend’. The word “safari” simply means ‘travel’.

In Nairobi, the capital, the sprawl of buildings and roads vie unsuccessfully to unseat the tenaciously luscious and abundant greenery and the stretches of fertile deep orange soil. Meanwhile the coast is all white sand and sapphire waters, with humid, hot weather all year and a darker, dryer soil. Here you’ll find rows and rows of laden coconut trees and families of monkeys casually causing mischief on any street corner. The centre of the country is dominated by the Great Rift Valley and there are also highlands and great plains, like the famous Maasai Mara, named after the nomadic pastoralist tribe, the Maasai.

Throughout the trip, my partner was struck by how much the country had changed in the time he’d been away from it, behaving a bit like a man returned from a decades-long war: “do you know how much a tuktuk ride used to cost?! “This used to be a dirt road, look at it now!”. The first change he noticed was a new tarmac toll highway from the airport to downtown, creating a high-speed route into Nairobi for international visitors. It was built thanks to a public-private collaboration between the Kenya Government and the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC). The CRBC will receive all the toll payments until their investment is recouped. Throughout the country and the region more widely, the influence of Chinese commerce and development has increased.

The history of foreign powers involving themselves in Kenyan infrastructure is not a new one. The country’s beauty, fertility and abundance has been attracting outsiders for centuries now. Arriving by sea on the East African coast, various invaders and colonisers have tried to impose themselves on what is today known as the country of Kenya (though its existence as a nation state, rather than a collection of different communities, was fabricated by the British). As early as the 7th centiry, Arab merchants established trade along the East African coast, then Vasco da Gama took charge of the coastal trade on a visit to Mombasa at the turn of the 16th century. The coast later went under Omani control. At the end of the 19th century, the British East African Company was granted a charter, which marked the beginning of an aggressive period of colonisation that would last until the 1960s.

There was resistance pretty much throughout the British colonial period, coming to a head In the 1950s and ‘60s through a network of dissenters who came to be known as Mau Mau. Through underground networks they coordinated to rise up against the British using tactics such as civil disobedience and targeted attacks and intimidation, coupled with consciousness-raising art and literature. The British establishment dismissed the uprising as terrorism and reacted violently, imprisoning huge swathes of the population, particularly Kikuyus subjecting them to torture, rape and murder. According to Unbowed, a book by Kenyan environmentalist Wangari Maathai that I will write about more in the book section, four thousand people died as a result of Mau Mau rebellion activities, of which less than 100 were British. Some scholars think 100,000 Kenyans died as a result of the subsequent British crackdown, and many more were left traumatised. (The details are harrowingly documented in Britain's Gulag: The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya by historian Caroline Elkins. The essays of revered Kenyan scholar and author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o explore the deep cultural effects of British colinialisation on the people of what came to be known as Kenya.)

The country finally won independence in 1963, but the rich and diverse land is still highly desirable for foreign developers, and much of it is still wrapped up with foreign investors. Many imprints of colonialism remain. Settlers forced indigenous farmers to leave the land that had been sustaining them with nutritious crops like millet, sweet potatoes and greens and took it over to plant cash-crops like tea and coffee, and non-native trees, like pine and eucalyptus for logging, which invaded the existing ecosystem and continue to disrupt it. Many large houses and compounds are owned by ‘KCs’ or ‘Kenyan Cowboys’, the colloquial name used for white Kenyans of British origin. There is also a significant population of Kenyans of Indian origin, many of whose ancestors were brought to East Africa by the British to work on projects like building railway lines.

Foreigners most frequently visit Kenya to experience going on safari and indeed the abundance and range of fauna is dazzling. In the back garden of my boyfriend’s sister’s place we saw playful monkeys every morning and more of them by the coast. I learned where the phrase ‘cheeky monkey’ came from when a piece of mango was stolen from in front of me quicker than I could possibly react by a grey Sykes’ monkey. There are also the Vervet Monkeys, with their distinctive blue bums, and the more uptown Colobus monkeys, who look completely different with their long black and white hairdo. They have no interest whatsoever in consorting with humans and their food: according to Omari, a local guide we met at the coast, these monkeys won’t even eat a fruit if it has a scratch on it.

We went to Nairobi National Park, a nature reserve on the edge of the capital, framed by skyscrapers. We were very lucky to see two lionesses sharing a girls’ breakfast in the form of a zebra they had just killed, and whose insides they were merrily ripping out. I learned that in the lion community, the females are much more effective hunters than the males, who tend to laze around much more. Later in the trip at Lake Naivasha on the edge of the Rift Valley, we had an excellent guide named Faith, who lamented the clumsiness of the male lions when hunting: “it’s really a shame that the males insist on being the ones to teach the sons to hunt,” she said, “because the lionesses are much better at it.” Man-splaining is not species-specific, it would seem.

We also saw wallowing hippos, stalks, ostriches, antelopes, wildebeest, zebra and some magnificent giraffes.

Kenya, as mentioned above, enjoys wonderful and varied produce, and food is a huge part of the culture. Staples include ugali, a pulp made of cornmeal, which can be eaten with the hands and used to scoop up other elements of the dish, like sukuma wiki (meaning food that pushes you through to the end of the week), which comprises collard greens cooked with onions and spices. There’s Nyama choma, slow-cooked grilled meat, most usually goat (the attitude to meat is quite different: there is a respect for the animal and usually all parts of it are used carefully). There’s also a big Indian influence on the cuisine and spiced pilau rice and fresh chapati are among other favourites. As in France, food is talked about often and its relation to the land is understood. As in the French language, many Swahili phrases evoke food. I liked when one friend suggested we were “eating life with a big spoon”.

At the coast, we ate fresh food every day, and when I tasted the pineapples and mangoes, I realised that any imported version I had tasted before was not really the same thing at all. In fact, it got me thinking about what sad half-reflections our projections of tropical culture and geography are in the UK: loud-coloured pineapple print t-shirts, plasticy-smelling inflatable palm trees, outdoor lidos made for the few weeks we have real sun, charcoal barbecues that we can hardly use.

—

Throughout the trip, I was very lucky to be in the company of locals, not least my partner’s sister, Ndiko, who runs her own travel company and can help you with everything, from the best place to stay by the beach to your visa application. If you are planning a trip to Kenya or are inspired to, I highly recommend going via her company Winda Guide.

In fact, just like the lionesses, we met a lot of Kenyan women leading the way. In the last few days we went to Lake Naivasha on the edge of the Rift Valley and did a guided walk around Crescent Island, home to animals like hippos, giraffes and the blue-bummed monkeys. Our guide, Faith, who told us about the ineptitude of the male lions, was knowledgable, welcoming and hilarious. She told us about the problematic bachelor hippos who get cast out of wider society for toxic behaviour, like attacking fishermen; she explained about the polyamorous tendencies of waterbucks, who don’t live long and thus adopt a YOLO attitude to their love lives; the romantic fish eagles who kill themselves when their partner dies and so on.

She is an environmental science student and has big plans for working in environmental conservation, inspired by Wangari Maathai, whose book I will write about just below.

Thirty-second book club

I didn’t know the name Wangari Maathai until relatively recently, and now I do I think everyone should know it. Born in the Nyeri District in the central highlands in what was then colonial Kenya, she went on to be a doctor of science, a pioneer of the Green movement, a trailblazing politician and a fearless social activist and the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Some years before her death in 2011, she wrote a memoir called Unbowed, in which she talks about her unrelenting fight to protect Kenya’s biodiversity, while also pushing for social equality and inclusion. She is great company and through her extraordinary life, I felt I got a deeper understanding of the history of Kenya.

“Trees have been an essential part of my life and provided me with many lessons. Trees are living symbols of peace and hope. A tree has roots in the soil yet reaches to the sky. It tells us that in order to aspire we need to be grounded, and that no matter how high we go it is from out roots that we draw sustenance.” — Wangari Maathai, Unbowed

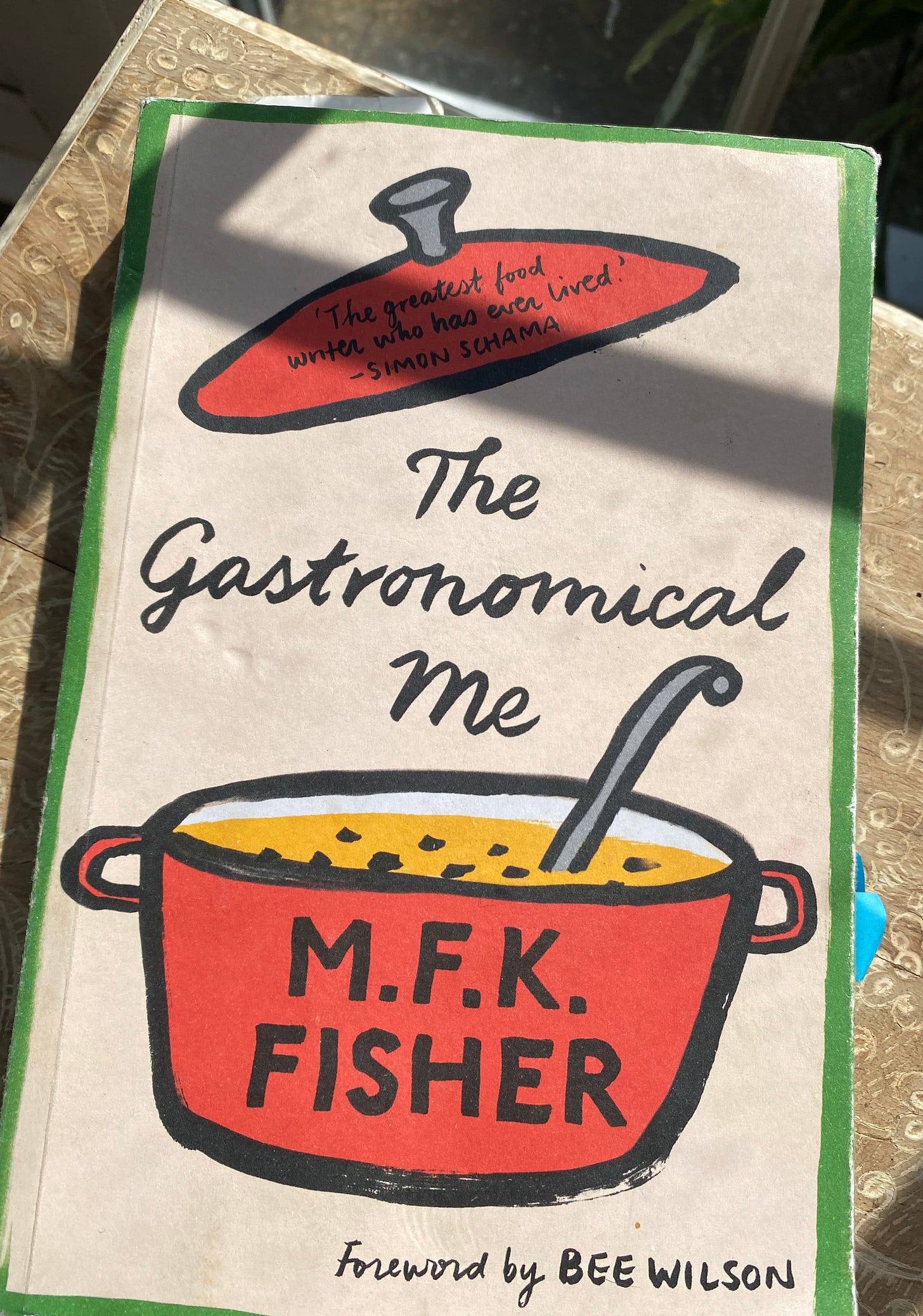

My other piece of holiday reading came courtesy of my dear friend and wonderfully supportive Pen Friend reader, Kathy. In late February, she sent me an email with the subject line: M. F. K. Fisher. I had sadly also never heard of this author who W.H.Auden described as America’s greatest writer. She was a Californian who spent many years living in France and who wrote about food. Or rather, as far as I can tell, she wrote about life as viewed through the prism of food and drink and dining. Here’s what she said about The Gastronomical Me, the 1945 book that Kathy recommended to me.

"People ask me: Why do you write about food, and eating and drinking? Why don't you write about the struggle for power and security, and about love, the way others do. They ask it accusingly, as if I were somehow gross, unfaithful to the honor of my craft.

The easiest answer is to say that, like most humans, I am hungry. But there is more than that. It seems to me that our three basic needs, for food and security and love are so mixed and mingled and entwined that we cannot straightly think of one without the others. So it happens that when I write of hunger, I am really writing about love and the hunger for it, and warmth and the love of it and the hunger for it."

Thank you for reading these few impressions of my trip to Kenya. Next week I will be back in Paris and will let you know the latest from the pensions protests and so on. I’ve got some interesting visits planned next week and will let you know about some good exhibitions coming up.

If you like these letters, consider subscribing, sponsoring, sharing, as you see fit. Thank you very much to the kind patrons who have already signed up.

I hope you have a good few days, and find the biggest spoon you can muster for life this week.

Yours,

Hannah

“She spent the first couple of weeks of her freedom looking after my dog,”

One can NEVER retire from parenthood.

“…the most common words known in Swahili are hakuna matata,”

That’s funny! And a great philosophy…

“Street signs and bumper stickers are full of proverbs”

What a wonderful and effective idea…I wish we had them in the States.

“There was resistance pretty much throughout the British colonial period, coming to a head In the 1950s and ‘60s through a network of dissenters who came to be known as Mau Mau..”

As a child born in 1953, I heard of the Mau Mau…they were fierce resistance fighters and were feared throughout Africa…in fact many a nightly prayer ended, “And protect us from the Mau Mau.” The following quote succinctly explains the conditions that bred the revolt: ““To understand Africa you must understand a basic impulsive savagery that is greater than anything we civilised people have encountered in two centuries”― Robert Ruark

“it’s really a shame that the males insist on being the ones to teach the sons to hunt,” she said, “because the lionesses are much better at it.”

Even in nature the male-hubris raises its head.

As in the French language, many Swahili phrases evoke food. I liked when one friend suggested we were “eating life with a big spoon”.

Just a superb phrase and philosophy!

Thank you for introducing Wangari Maathai and M. F. K. Fisher. The photos and the sketch are wonderful, as well.

Lovely indeed to read your journal about Kenya. It made me looooooong to visit tooHannah.

Especially the fabulous wild animals. I loved the philospphical sayings on the roadsides and trees! We definitely need one for the woods here saying " no hooting" the owls must be feeling very sexy as they hoot with impunity at each other from dusk till dawn , every night,

I know theres a type of owl called a horny owl and now I know why!

Talking of breeding , the frogs are little better, croaking and blowing up their necks like an anglo bubbly bubble gum in a teenagers classroom!😂

The seals take over by day barking and honking at sea all day! Great wildlife too up in Scotland but a lot wetter and colder and too high up in the trees to see !

Welcome back to both london and Paris darling Hannah and lots of kind thoughts to your mum on her retirement. X